Ethical Data Science

Thanks to the coming of the information age, we live in a constant stream of information overload. It seems quaint and antiquated that there used to be a time when the newspaper would provide all the news, and one could read every article.

Then, with the option of various newspapers came the perils of choice: Who do I trust to give me the relevant information? Preference comes with the crowd we frequent, the views we hold, and the politics we vote for. The internet provides more news sources that could ever be read, so we have algorithms to decide what we want to read. You may still subscribe to an online newspaper like the New York Times, but you will inevitably come across information published elsewhere, as chosen by algorithms at facebook or google.

While the news may be written in a neutral, informative way, the choice of which news to read is much harder to perform without bias. The president may go to a dozen events in a day, and we don’t want to read about all of them, but some will affect our view in different ways than others. A remote country like Eritrea may be presented as prospering or in dire conditions, depending solely on whether we read that the end of the war brings new business, or that the standard of living is still well below the global average.

The purpose of this article is to formalize a need for ethical recommender systems in an era of constant information overload. Search tools, just like newspapers, must strive for neutrality, but there are new hurdles that newspapers didn’t have to consider. While this article specifically considers news, the same ought to be applied to any piece of information that reaches us through selection algorithms. Scientific articles can be sifted with the same methodology, informative photos and videos, and even pure entertainement, like Dilbert jokes.

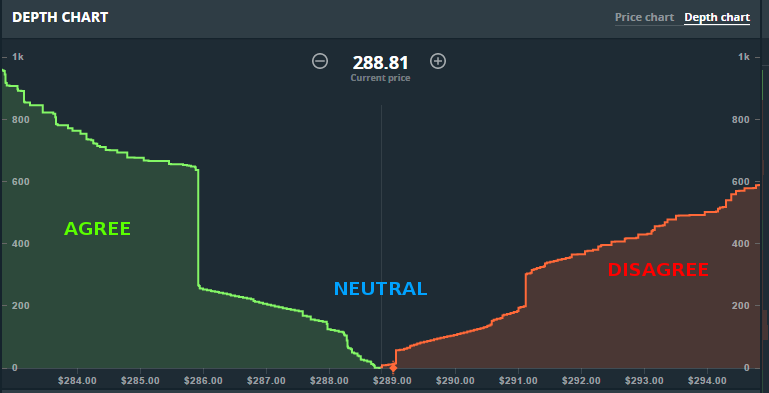

The first problem is “Affecting opinion”. While chosing which news to display, a neutral recommender must give the explicit option of articles in line with my views, but also the average view, and the opposite view. The concept is similar to understanding the market depth chart, which shows the current price of a stock being traded, and also a histogram of standings on either side.

The second problem is “Hearing what you want to hear”, also called the social bubble. This happens by displaying selective views on a given event. Given a specific news topic, a neutral recommender must not give what we may want to hear (as an information search engine does), but rather give us a representative spectrum with regard to public opinion.

Thirdly, due to information overload we are increasingly sussecptible to access information which itself is misleading. People are susceptible to numerous forms of manipulation when it comes to their view of the world. To solve the “Unethical Information” problem, any news articles inciting anger, contatining fake news, or manipulating the reader with logical fallacies should be weeded out by aggregators, instead of being snowballed through digital media.

If agreed upon, each of these aspects can be quantified, codified, and implemented. A digital information aggregator can then put it all together with a scrolling system, showing us as much as we want to hear sorted by relevance, and monitoring what we click on not to maximize hits, but to ethically inform.